Catwalks and Copycats: Trends and The LawBy Georgia Devon-Spick

This week #PFW marks the denouement of the infamous three lettered acronym-ed tour. From New York to London, Milan and Paris, designers have proudly showcased their AW15/16 collections on catwalks and exhibitions alike. Reporting has focused ( in addition to the obiter comments on Kim’s hair colour), on identifying the respective A/W trends, which, inevitably, are swiftly to be cloned onto High Street mannequins.

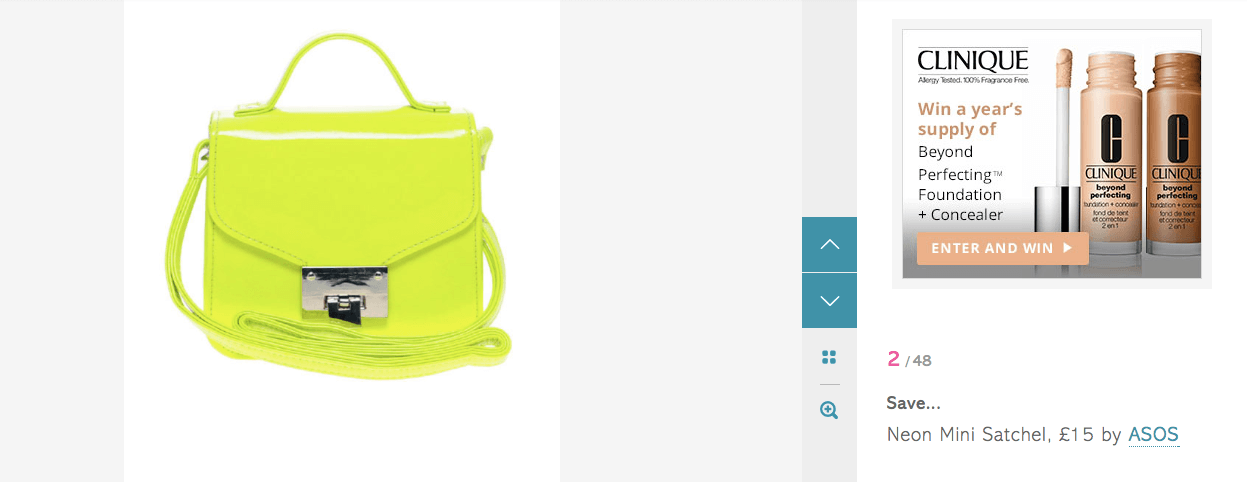

This predestined duplication is well documented in any magazine with a fashion section, (think ‘Splurge’ and ‘Save’ features). But when is this copying deemed as subscribing to a trend and when is it theft? As a designer are you happy when your design is is ‘spun-off’ (quite literally) to exist on the high street at a fraction of the price? Does this serve to verify and credit your abilities as a trend-whispering, snake charming Fashionista? Or is it quite clearly ripping off?

Fashion appropriately operates in ‘seasons,’ indeed, trends do run in cycles but where does the law fit into this? Dr. A Pandya from Taylor Rose Law, explains:

“Trends and copying territory, are important generic considerations in determining what is actionable as the tort of passing off. The generic formulation, however, still applies: (i) Is there an identifiable good will? (ii) is there a misrepresentation as to the source of good will (so as to confuse prospective purchasers) and (iii) is there damage to the party holding the good will? In a basic approach much will turn on why consumers would seek to purchase a particular piece of fashion merchandise.

Where a there is a general trend in fashion on the face of it there will not be passing off, unless some individual has goodwill, by being its clearly identifiable originator, linked to the trend. The uniqueness of each design and its ‘attributability’ to a single person or a group of persons may result in the courts assigning goodwill to the persons that the law will deem fair to protect, despite the restrictions on trade to others that would ensue. ”

Both Diane Von Furstenberg and Christian Louboutin have avidly protected their designs. Diane Von Furstenburg has had a long battle with the high street and has filed cases against Forever 21 Retail Inc., (who have a lost list of claims against them) Target Brands Inc., and Mango On-Line Inc, for their replication of her work.

But it’s not just the High Street that’s attempted to cash in on designer collections. For two years the then ‘YSL’ and Christian Louboutin were head to head in court following YSL’s use of Louboutin’s iconic red sole. In September 2012, the U.S Federal Court of Appeals ruled that Christian Louboutin could protect its iconic redsoled shoes from copycats, except when the shoe itself is red.

YSL’s legal representatives stated: “YSL is pleased to see now completely closed this action that had put at risk the ability of fashion designers to trademark color, as well as to now have confirmation from the Court that it is entitled to continue to sell its unique and famous monochromatic red shoes.”

So where does this leave us for the future of Fashion? Is Fashion now stifled as having to be uber original, ( whatever that means) which arguably defies its cyclical nature? Fox Williams, with the recent decision in Superdry v Animal have broken design rights infringement down into five things we can learn from the case:

1. Changing a certain number of features from the original on the copied product is not enough to avoid infringement of Community unregistered design rights. This is because the test for infringement is one of “overall impression”. For example, changing the length of a placket, adopting buttons instead of a zip, and changing the width of drawstrings did not avoid infringement in this case.

2. Parts of clothing can be protected by design rights. This means that one feature or a number of features of an article can be protected such as, in this case, the fastening mechanism of a gilet, its collar, and the way a hood is attached to it. In this way, the essential characteristics of a garment can be protected.

3. Registration acts as notice that you have rights in a design. Important designs can be protected by registration provided the application is made within a year of first marketing. EU wide registration protection is relatively cheap and quick to achieve.

4. Branding (such as a logo or a name) is generally ignored by the courts when assessing design infringement (unlike trade mark infringement and passing off) except in cases where the simplicity of the design is a feature such as in an Apple iPhone.

5. It is still necessary to show copying to succeed in an infringement action for unregistered design rights unlike registered design protection where it is not necessary to show that copying has taken place to succeed. In this case, Animal was found to have copied.

If you’re Moschino and you’re annoyed say Nasty Gal have copied a few of your designs, I don’t think you’ll care all that much, because they’re obviously ‘knock-offs,’ and in fashion, especially with something as distinctive as this collection, the real value lies in the original piece. However, for young designers copying is a lot more frustrating, and with Instagram and other social media platforms, they’re increasingly at risk of having their work copied. I accidentally opened Pandora’s Box when I posed this question to young designers through twitter, as there was an outcry of finger pointing of all the people who had been both victims and perpetrators. Make sure you don’t fall victim to the blurred lines of of copyright infringement and know your rights:

http://www.own-it.org/uploads/files/244/original/The_IP_Guide_to_Fashion.pdf